Block Letters and Other Tools of Literacy for a New Day—Part Two

By Charles Peek

The “Ole Miss Brick” about which I wrote in the last post—the second of the awakenings to come my way this summer in the form of a block—was not the only meaningful block of this summer. It was preceded by another and followed by two more.

With each, I was reminded that, when I was first learning to write, we all printed using both upper-case and lower-case letters, often printed out together: Aa, Bb, and so forth, only the letters were more like the block forms one now sees on digital readouts whose shapes always seem to me retro. It’s been a journey from there to this summer’s messages, which have not seemed to come from block letters but from blocks themselves.

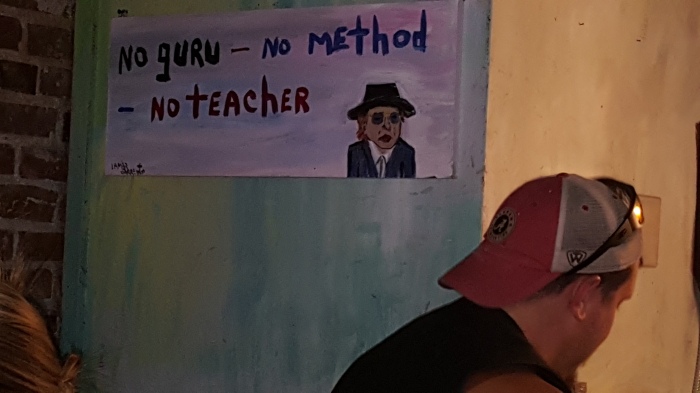

The first block was really a rectangular drawing on the wall of B.B. King’s Memphis restaurant. The drawing pictures a person under the caption “No Guru No Method No Teacher”.

[Insight at B. B. Kings]

[Insight at B. B. Kings]

The message reminded me of a favorite Camus comment: whoever has no character must have a method! Or of Jesus’ remark that, having received the Holy Spirit, we would no longer have any teachers.

Seeing the sign while listening to a fine blues singer and band suggested to me how much the sign was not a repudiation of guidance or example or mentoring but rather an assertion of holding oneself accountable for learning.

Too often in schools today, teachers are blamed for students not learning. Too often it is true! But ultimately learning is the responsibility of the learner. “No Guru No Method No Teacher”!

Later, while we were in Milwaukee for August, we visited the Rashid Johnson exhibit at the Milwaukee Art Museum. Johnson does a great deal of his work on square white ceramic tiles that together form a grid on which the stunning facades of glass and mirror and fabric and rich designs take shape. The whole of one display that occupies an entire gallery are blocks with the faces of anxiety sketched in…or, in some cases, missing—the faces of those lost on the journey.

[Rashid Johnson ‘s portrait of anxiety]

[Rashid Johnson ‘s portrait of anxiety]

The Rashid Johnson exhibit was a bold move, on both his and the museum’s part, given the racial history of Milwaukee; it was mounted as part of the city’s 50th anniversary commemoration of the Civil Rights marches for fair housing led by, among others, Fr. Groppi. We’d look up and there would be a Milwaukee bus advertising the commemorative events, including the exhibit–in rectangular block posters.

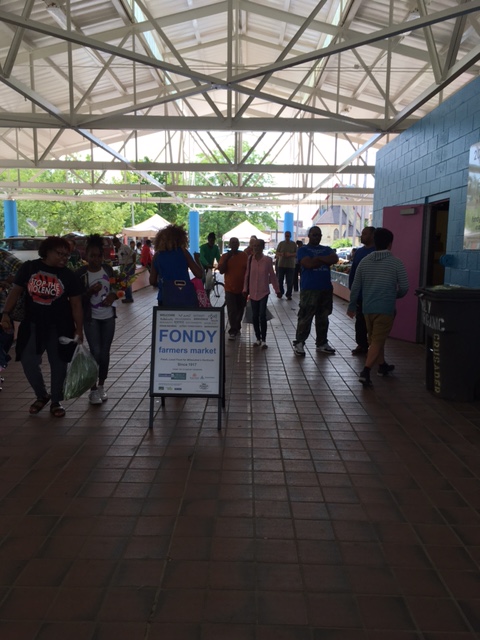

After a panel discussion of the exhibit, we met panelist Venice Williams who, in her talk, had mentioned her cosmetic work with the Shea Butter—a substance which forms some of Johnson’s more powerful (and plentiful) imagery, noting that she has a seller’s stall at most of the area Farmer’s Markets. In the course of our conversation, she invited us to the Fondy Market to see her wares but also to enjoy the other pleasures of the market.

The following Saturday, after watching Willie and Greta take a swimming safety lesson, we drove over to Fond du Lac, a diagonal through a lot of Milwaukee, to the market where we met Venice again.

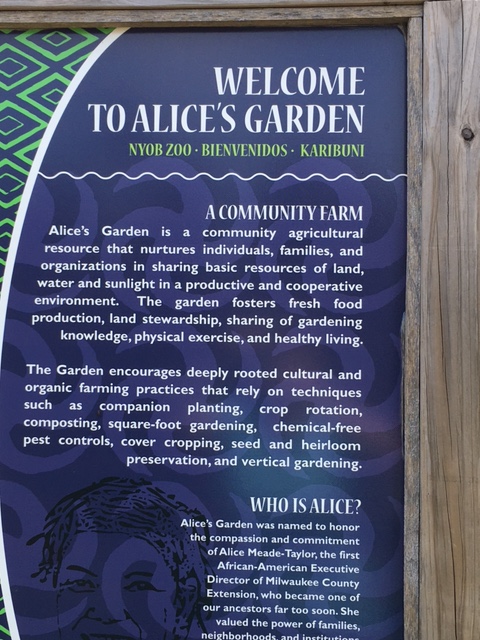

On this occasion, in our conversation she invited us to visit her Alice’s Garden a few blocks away, a community garden enterprise on a former vacant lot. This garden, like Growing Power and the Mayor’s Garden and the Farmer’s Markets, originated in the desire to alleviate some of the urban food deserts that racism has helped create.

[Entry sign at Alice’s Garcen, Milwaukee]

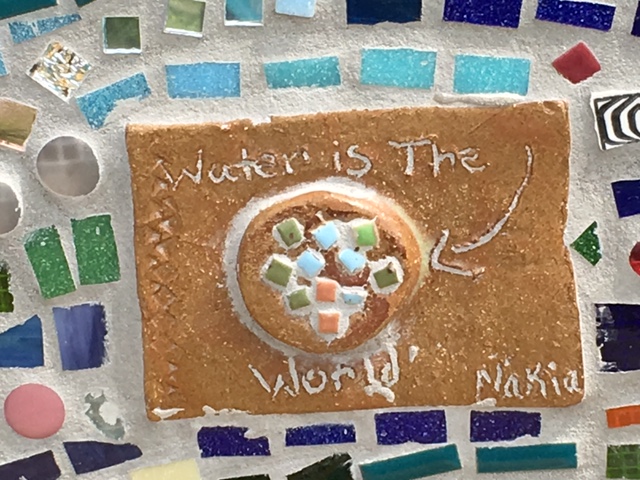

There in the midst of the garden was a shelf fronting a set of block tile squares that formed a panel where enterprising ceramicists (my guess is youngsters) had put messages on blocks and medallions. One message in particular struck a chord with me, the message “Water is the World.”

[“Water is The World” by Nakia in the ceramic comments on Alice’s Garden]

[“Water is The World” by Nakia in the ceramic comments on Alice’s Garden]

Water is a subject dear to a Nebraskan’s heart! But, because we were in Milwaukee as I wrote this, we were missing things going on in Nebraska while we are gone. Foremost at that moment was the ordination to the priesthood of our friend Tony Anderson who graduated from Virginia Theological Seminary this spring, the latest step in growing into his Baptism by water and the spirit. What we missed almost as much, however, was the huge protest march in Lincoln against the dreadful Keystone XL Pipeline that threatens our water and land and runs roughshod over sacred Native ground and the property rights of ranchers and farmers.

It’s hard to choose which of those issues is most important, but for long- range economic consequences, it is hard not to think the potential destruction of the Ogallala Aquifer isn’t high on the list. Destruction…or, if the water wars in fact come, then the theft of our water! These concerns are what prompted Presiding Bishop Curry, in his visit to a similar site in the Dakotas, to preach on “Water is Life.” And here we were looking at a panel that read “Water is the World.”

![]() [Icon-like celebration of being set free at Alice’s Garden, Milwaukee]

[Icon-like celebration of being set free at Alice’s Garden, Milwaukee]

All these blocks—the Ole Miss brick, the ceramic blocks that structure Johnson’s art, the message medallions at Alice’s Garden—seem now to me like the old block letters I learned to write. They are each a new entry into a new literacy, a new invitation to see the world in a new way and to appreciate different ways of communicating common human need, longing, and affection, different ways to cope with joy and loss. They are, like writing, like the block letters that began our journey to literacy, a means of liberation.

It’s been an education! Sincerest thanks for the Doctor of Letters, honoris causa, bestowed by BB King’s wall art, Jay Watson (see the previous blog), Rashid Johnson, Venice Williams, MAM, and Alice’s Garden. Believe me, I’ll work more on my blocks, not maybe my block letters but certainly the learning blocks that keep extending my literacy.

And Miss Omler and Miss Noren, surely by now ahead on the journey, since you started me on this path in first and second grades at Orrington School in Evanston, Illinois, not so far from where I am writing—I hope you will think I’m making some good progress or, at least, keeping up. Along with my block letters, you taught me that there are always new ways the world teaches us.

[Fondy Market, Milwaukee]

Milwaukee, Wisconsin

September 2017

[Chuck at the Ole Miss Power Plant]

[Chuck at the Ole Miss Power Plant] [ Friend Grayson Schick with other regular conferees at the old Yokna Inn near Oxford]

[ Friend Grayson Schick with other regular conferees at the old Yokna Inn near Oxford] [Chuck with Theresa Towner, the late L. D. Brodsky, and Jim Carothers at FY]

[Chuck with Theresa Towner, the late L. D. Brodsky, and Jim Carothers at FY] [Brunch hosted by Abadies in Oxford–Chuck, Jack Barbera, Jennie Joiner, Dale Abadie, Nancy Peek, Colby Kullman, Bob Hamblin at far end, Ann Abadie, Theresa Towner, Jim Carothers, John Lowe, and Bev Carothers]

[Brunch hosted by Abadies in Oxford–Chuck, Jack Barbera, Jennie Joiner, Dale Abadie, Nancy Peek, Colby Kullman, Bob Hamblin at far end, Ann Abadie, Theresa Towner, Jim Carothers, John Lowe, and Bev Carothers]