https://mail.google.com/mail/u/0/#inbox

Things Faulkner, starring Robert Hamblin: An Appreciation

By Chuck Peek

Outside the world of teaching scholars, both the public and the upper echelons of administration show little understanding that, whatever your discipline, your professional circles are probably your greatest source of encouragement, the place where you learn most, some of the other people in your discipline becoming your closest friends. I’ve been blessed to be a close part of both the Cather and the Faulkner societies, as well as a small part in conference on composition, Western Lit, and Hemingway.

As you will see if you follow to the end, something special has drawn me right now to the Faulkner world, where I was first drawn by Lee Lemon, who chaired my dissertation, and the late Jim Roberts, the “Faulkner Guy” at Nebraska University when I was there (1960-197). That’s where Jerry Parsons once saw me coming out of my office and, knowing I was working on Faulkner said, “Well, if it isn’t Lump Snopes.” We became friends anyway!

My relationship with Jim Roberts was never lukewarm. He could be very generous—Nancy and I were invited to parties at his home and, after I’d graduated, he bailed me out of financial woes one summer by commissioning me to write the Cliffs Notes for Catch-22. But he could be vindictive, too—scuttling the University of Mississippi Press’s intention to publish my first work on Faulkner, the heart of which he’d heartily approved when he served on my thesis committee but wasn’t chosen as its chair.

What tipped the balance in favor of remembering his more generous self, however, was that in the late winter of 1973-74, he tipped me off that Ole Miss was going to have a conference on Faulkner the summer of 1974…he thought I might like to go. A forever “thank you,” Jim!

That first conference, Faulkner and Yoknapatawpha, overbooked—they had to offer it twice in back-to-back weeks, and unlike most conferences on single authors, they are still offering it every summer yet. It may be the longest-running single author conference in America. I went the first three of its fledgling years, 1974, 1975, 1976. There were still lots of folks around who had known Faulkner who came to the conference to tell stories, among them Faulkner’s cousins Jimmy and Chooky, his supposed bootlegger Mottee Daniels, and Faulkner’s doctor, Chester McLarty.

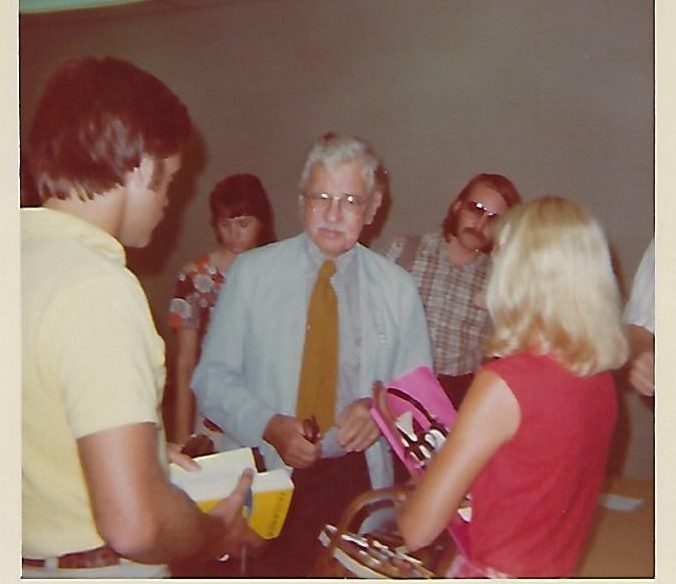

Jimmy Faulkner and Chuck Peek at Rowan Oak

Jimmy and I tried for years to connect so he could come up to Nebraska and go pheasant hunting, and the good doctor was later embroiled in the controversy between him and Jimmy over the Faulkner-on-the-bench sculpture on the square and whether it was worth the loss of a good tree or even “looked like Brother Will.” The good Doctor Chester McLarty even chaired a panel entitled Oxford Women Remember, until in later days the women grew older, their hair bluer, and no matter how Chester prompted them, recall seemed more and more to fail them, until one day Jim Carothers whispered to me, they’ll have to retitle the panel.

Universities like Texas and Virginia had run a quarterback sneak on Ole Miss in terms of their libraries and faculty, so Ole Miss turned to its unique offering—the place where Faulkner lived and wrote. There were picnics on the lawn of the Howorth family, just across from Rowan Oak, or at Rowan Oak itself, sometimes after a walk from campus through Baily Woods, as well and grand tours or the town or nearby Faulkner haunts or a trip to the Delta, but there was always a cast of stellar speakers those years, including his first biographer Joe Blotner and the editor of The Portable Faulkner that had helped him win the Nobel Prize, Malcolm Cowley. They’d be joined subsequently by historians such as Shelby Foote and literary notables like Cleanth Brooks, Carvell Collins, Kenneth Holditch, Elizabeth Kerr, Thadious Davis, Philip Weinstein, Joe Urgo, and Louis Rubin.

Over the years, this conference, centered on Faulkner, nevertheless invited contemporary writers to read and give their own homage to Faulkner’s influence. Mississippi and Southern Writers, like Eudora Welty, Willie Morris, Elizabeth Spencer, Joan Williams, Barry Hanna, Larry Brown, P. J. O’Rourke, and Clyde Edgerton, joined others like William Styron and John Barth, and their readings voiced the spirit of conference.

So did readings at Kullman’s “Fringe Faulkner,” where the poetry of L.D. Brodsky and Bob Hamblin, along with some of mine, was read, and it usually fell to Jim to eulogize those who had passed, including Betty Harrington, who often gave dramatic readings of Faulkner’s work. She and Evans hosted the “faculty” at their home each conference.

Often, we’d meet after the evening sessions for a few drinks at one of the local watering holes or before the sessions for dinner with other participants or one of the speakers. It was grand. And that first year, I got to interview Malcolm Cowley. Sadly, the video of that was accidentally disposed of, but my own tape recording of it yielded an article for The Faulkner Journal, after Jim Carothers had run it through a recording analysis at the police station to pick up some of the names Cowley spoke of through the hum of the recording.

Malcolm Cowley 1974 F&Y Ole Miss

One of those years, Mottee led me around the square in Oxford on election night—every little shop a campaign headquarters for someone, and a huge chalk board set up on the east side of the courthouse where men climbed up and down ladders chalking in the most recent vote count for every office in Lafayette County. Another year, he invited Nancy and me to bring our young son out to his place to fish in his lake.

Then, I left Northern Arizona University where I had been teaching Philosophy and American Studies, came to Kearney, Nebraska, and assumed the role of Rector of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church. Late summers, with the Diocesan church camp and the preparations for “back to school” time, didn’t allow me to be gone, so I missed the conferences 1976-1985.

Oxford had been one of my favorite watering holes. After I’d been to rehab for alcoholism in 1986, I decided to test how sober I intended to stay by going back to F&Y. A drive straight through from Kearney to Oxford, a conference highlighted by the whole passel of scholars who had taken up the leadership of Faulkner Studies, and I had a wonderful time with them all—sober.

One of the speakers, an up-and-coming Black scholar from Yale, James Snead, had given a provocative talk, and even after 9 years on hiatus, I’d dared to make a few comments on his talk at its close, and that’s how I first met Noel Polk, who was sometimes called “the Dean of Faulkner Studies,” by some affectionately, by some sneeringly. Noel had taken to some of my remarks and wanted to meet and have a chat about them with me. He never failed to respond to my Christmas and Easter blogs, and years later one of my saddest times was when Noel was dying and Nancy and I drove down from Oxford to see him one last time.

**

Even though I’d been to the first three conferences, it was clear after my hiatus as Faulkner studies took shape, that I was like a newcomer. But the conference chair, Evans Harrington, urged all of us “newcomers” not to be shy—everyone is welcome in the conversation, he said. So, one breakfast time, I got my tray, looked over at three fellows sitting at a table for four, their noses deep in the sports pages of the newspaper, and, though they were not looking like they were going to welcome a fourth, I sat down anyway and told them Evans had sent me.

They turned out to be Tod Oliver, Jim Hinkle, and Jim Carothers, all three also Hemingway scholars, Oliver and Hinkler the more so, Tod a founding member of the Hemingway Society and an editor of the Hemingway Review, Hinkle whose name graces a scholarship offered by the Hemingway Society. Both are gone now.

Jim Carothers became and remains one of my best friends, along with his wife Bev and daughter Cathleen. Together, we’ve eaten our way across Oxford and on into northern Mississippi, and into “furren” places, as well as taken in worship at St. Peter’s (where Faulkner and his wife nominally belonged and Joe Blotner’s biography has him taking notes in his Book of Common Prayer during sermons), sometimes with Terrell Tebbetts, Grayson Schick (more later), and Charles Reagan Wilson, with breakfast afterwards sometimes enjoying the Abadie’s hospitality, sometimes at the Bottle Tree and the best blueberry muffins anywhere. If you wanted to know anything about Faulkner’s short stories—which is where I like to start students—you go to Jim and his student Teresa Towner’s book.

By 1987-88 I was back in academe, teaching at then Kearney State College, now the University of Nebraska at Kearney (at least until the present system administration guts its arts and humanities, but that’s for another blog), which meant I could go to the conference every year, 1988-2019 (and two by zoom after that), sometimes alone but most often with Nancy and sometimes with the family…39 in all, at least 30 assisting with Teaching Faulkner for the conference not counting other times for the SAKS Institute, and a couple of times as chair of a panel I’d put together or as speaker on the “main stage.”

So began my enjoyment of so many participants, among them Bill Shaver and Jim Campbell, to whom Bob Hamblin and I dedicated our book on schools of Faulkner criticism, and that same inimitable Dr. Grayson Schick, a psychoanalyst who is known to take no prisoners, including those responsible when the pool is not functioning properly. Early in my coming back to F&Y and on Grayson’s first trip back to the south where she’d been raised, we drove together to the Memphis airport, bonding over the emotions of our experience, the bonding become a life-long friendship.

Too, there was Greg Perkins, whose interest was so sparked he often footed the bill for a conference cocktail hour in addition to the one Colby Kullman and Professor Noyes hosted. Theresa Kelly, from Selma, a fine teacher in her own right, invited me to tag along to post-parties at Jimmy Faulkner’s. Groups of us would get to one of the Phillips Grocery Store sites for cheeseburgers, or out to an old inn along the river that gave Yoknapatawpha its name, or later on to the Ravine, or down to Old Taylor for catfish, the years of accumulated grease the deep frier had popped up on its walls no doubt grandfathered in, almost always an hour wait to get in. Almost always, those of us from Kansas and Nebraska would get together, one of us treating the others to dinner—we called ourselves the Kansas-Nebraska act!

Among the outstanding speakers those days, Tatiana Morosova, who came with the delegation from the Gorky Institute, shepherded by Sergei. Sergei, after much discussion (Glasnost had begun), allowed me to take her off campus to the Downtown Grill for lunch. We passed a large home on the way and she asked me how many families would live in a house that large. She was amazed when I said “just one—and possibly just one person, likely a widowed woman.” The Down Town Grill’s “praline surprise” desert covered a whole plate—as the ice cream began to melt, she just stared at it. I could hear her thinking, ‘decadence’! but she didn’t wait too long to enjoy her whole plate.

There was Arthur Kinney (teaching a graduate seminar in Shakespeare at NYU and one in Faulkner at Johns Hopkins, where John Irwin also taught), Carl Rolyson, author of the most recent and excellent biography; and Caroline Carville, teaching literature at Rose-Hulman, an engineering school! Or later, newer scholars, the Elvis-sounding Taylor Hagood, the fine blues player and scholar Adam Gussow, Jim’s students Theresa Towner and Jennie Joiner, and one of Noel’s students, come into her own, Lori Watkins Massey.

There had been no African Americans welcome at the first F&Ys—the Faulkner nephews didn’t want to be part of that— “we didn’t always see eye to eye with Brother Will”! But Blyden Jackson soon broke that barrier. Similarly, there was not much mention of homosexuality in Faulkner’s work or among his friends until the later work of John Duvall and others. Recent conferences included the topics Faulkner and Richard Wright and Queer Faulkner, and fairly recently Ole Miss joined a number of other universities exploring how, all too often, their heritage was built on slave labor, slaves coming to campus with both the faculty and students, and workers laying the actual foundations for the buildings they also constructed. This has been one of the most interesting features of recent conferences, and prompted me toward the end of my appearing there to put together a panel in which my part was to address Faulkner and Black Nationalism. (The panel was lauded, my other presenters ending up in the publication of the conference—absent mine!)

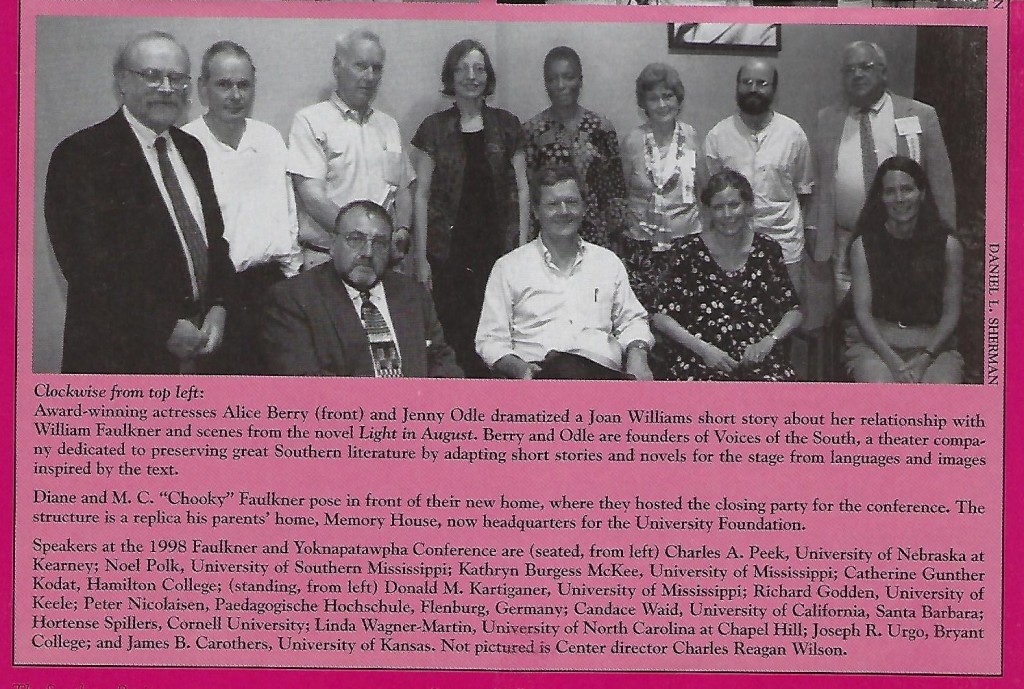

Southern Register photo of the speakers for the 25th F&Y Conference

The attractions were not just the notable speakers from here and abroad; there were locals as well: Colby again, who was a drama and a Tennessee Williams scholar in his own right, and his friends from Sweden via Spain, Helge and Marianne Steinsvik—of an evening, we used to take coffee out on the balcony of Richard Howorth’s Square Books where we could, before it came to an end everywhere, enjoy a smoke. Local Joan Wylie Hall ran the SAKS program for area teachers and twice asked me to speak to them, and it was Joan who kept the Carothers and the rest of us apprised of Colby’s death and the accolades it evoked.

When Bill Ferris was head of the Center for Southern Studies (before his able successor Charles Reagan Wilson), he used to host the speakers on the night before the conference opened. One year, I got in too late for the van to Ferris’s house out by the cemetery. I arrived after quite a walk by foot, my polo drenched from the Mississippi humidity, so I had to put back on the sport jacket I’d carried with me. It was at one such dinner party that Francis Patterson confused me with Bob Hamblin…after all, he’s only about 6 inches taller than I. She was a lively and dedicated woman, who annually announced the Eudora Welty writing awards to young writers.

We are at the point in life where we are sorting through our memorabilia and disposing of stuff that our kids won’t want to sort or keep, but among the things we are hanging onto are the mementos of our “Faulkner Years”—the letter from Carvill Collins responding to a question about a book inscription, and apologizing for not being able to stop to visit in Flagstaff; a note from Evans Harrington to be sure to let him know when we’d be in Oxford on a special trip we were making over the Christmas holidays; a note from Joan Williams; and all the photos from China where I taught Cather, Faulkner, and Hemingway short stories (as well as American Film and Drama), two of my talks appearing in the journal published by Sichuan International Studies University, where Lan Renzhe, Faulkner translator, and I spent a day poring over how best to translate details in Faulkner’s work that still puzzled him.

The late Lan Renzhe, one of our great hosts during lecture tours in China

On the winter trip to Oxford, not only coffee with Evans, but a dinner on the balcony overlooking the square with Willie Morris on one side of us and a newlywed couple on the other. Wherever Willie was, there was a gathering and the spirits flowed. Every once in a while, a round of drinks would come to our table compliments of Willie. We’d raise a glass to him, he’d smile, and then, since I’d stopped drinking by then, we’d pass the drinks over to the couple. After an evening of that, the couple finally said enough was enough—they had some other plans for the evening!

In contrast, the next night, we went upstairs at the grill, only to find there was no admittance…there was a “big party” that had booked the whole balcony. The waiter who had stopped us went on to other duties, I looked into the area and saw it was seemingly empty, peeked around the corner to see what was up—and saw there the “party”—John Grisham and his wife, eating alone. This was not the only time this happened. At the conference, we planned a party one night, only to find the balcony was again “closed”—the Grisham’s again. Oh, the price of celebrity! But we had memorable moments at the Downtown Grill, where we often celebrated big achievements in our small circle of the Faulkner world.

True, we had our, well, wackier participants, often coming repeatedly. There was the couple who couldn’t keep their hands off each other, who explained they’d just been married, and who later confessed they’d never been married at all. Or the woman whose father accompanied her until they were both asked not to return. Or the speaker who got carried away describing her menstrual periods. Or the clinical psychologist, part of the medical staff at a New York Hospital using Faulkner to teach Abnormal Psychology, who brought his mother who came to events or went on tours in her slip.

One of those great wacky (in the best sense) moments occurred when Jim Hinkle arrived without a jacket—all the main speakers dressed up in those days—and Jim and Bev helped him buy the only one they could find—bright yellow. So, when Evan’s introduced Hinkle, he concluded: Jesus loves him for a sunbeam! Or when Carothers spoke, after his third by-pass, one valve from a cow, one from a pig, and one mechanical, and was called Professor moo, oink, click.

Perhaps others thought Jim and I floating in the pool at what was the Alumni House and became the Inn at Ole Miss belonged in the category of the wacky! Or perhaps they were just amused by Helge in his speedo. Or relieved that Grayson had found the pool open.

**

Finally, I get to the title and point of this blog entry. Nowhere in the early conference programs was there a session on Teaching Faulkner. There, also, were never any of the T-shirts that participants buy at many conferences. No one would be interested in a Teaching Faulkner session. This is not a summer camp, it’s an academic conference. But all that was about to change.

One summer, Bob Hamblin led a Humanities program on campus, the participants finishing their weeks together with a final week at the F&Y conference. One of those participants, Betty Kort, of Hastings, Nebraska, designed and produced a tee-shirt, and most of them came to that final week wearing them. This set up a hue and cry: academics asking why can’t we have T-shirts? And they have ever since, each becoming something of a collector’s item…several of mine sewn into a bed quilt by my daughter. (We haven’t gotten all the grandchildren to Oxford, but both our children and our daughter Noelle’s oldest son, and both her husband and our son and his wife have all been to F&Y and Oxford…and of course nearby Memphis, to B. B. Kings or baseball or Graceland.)

But Bob also knew the leaders of the conference. He’d received his Ph.D. from Ole Miss, did his dissertation under John Pilkington, and knew his way around. In the National Guard under Maury Cuthbert “Chooky” Faulkner’s command, he stood with other guardsmen as the thin line between James Meredith and the riotous protestors of Meredith’s enrollment, buttressed only by Evans Harrington and Duncan Gray, the Rector of St. Peter’s Episcopal Church, who also stood in the midst and succeeded in not letting the crowd move on to mob violence.

Bob kept pressing the question: can’t we have a session on Teaching Faulkner.

So, one year, they gave in. Late one afternoon, in the small moot court room at the law college, they gave Bob a “teaching Faulkner” slot, the title itself taken from a talk Sister Thea Bowman had given some years before, up on the third floor of the Court House if I recall rightly. Who would come to the late afternoon session allotted to Bob? Well, so many came that it overflowed the moot court room and spilled out into the halls.

F&Y began offering one teaching Faulkner session, and then added another. And Bob brought on others of us, at first one session being favored by high school teachers and the other by college professors, although anyone could go to either. I loved working with the high school teachers until we brought on Brian McDonald, himself a high school teacher, but I felt rewarded as well when prominent scholars like Arthur Kinney or Noel Polk or Virginia Hlavsa, or our beloved Ann Abadie would sit in on the session. And, as one of those drafted to lead these sessions would always announce, “Maybe you don’t have a teaching position, but if you love and read Faulkner, someone is bound to ask you why, and instantly you become teacher.” These sessions were often the ones participants noted as their favorite things about the conference.

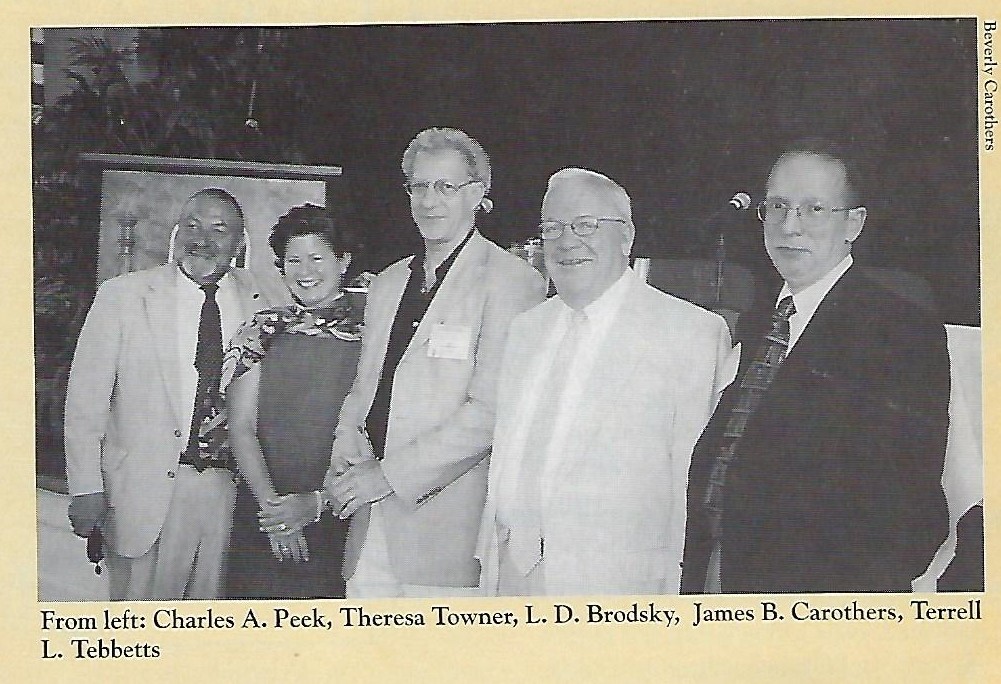

Teaching Faulkner folks joined by L.D. Brodsky, poet and collector

They remained a constant favorite under subsequent conference directors Don Kartiganer and Jay Watson, the conference being always blessed with fine directors who tried to balance its appeal to cutting edge scholars and to general readers, each a good scholar in his own right, and Don singing and strumming a ‘mean’ Barbara Allen, all of them shepherded by assistant director in perpetuity, Ann Abadie.

One of my favorite sessions on Teaching Faulkner occurred when Arlie Herron and I were teaching together. Arlie had played major roles in southern literary conferences, had a voice and bearing that stamped him as southern, and added so much to our sessions. But one year, the session began with a question, and Arlie said, that reminds me of a story by Eudora Welty, whereupon he opened his satchel, withdrew a book of her stories, found the line he’d been reminded of, and then decided we might need reminded of its context and, after flipping some pages—where to begin?—he began reading. He read the whole story. It was beautiful. And as he finished, I saw that we were out of time and thanked everyone for coming to another Teaching Faulkner session.

Bob Hamblin had invited me to join him in editing A William Faulkner Encyclopedia, and we celebrated its publication on his campus at Southeastern Missouri State University. I invited him to speak on my campus as a part of a Black Studies program, for which he gave a wonderful talk on Intruder in the Dust; he and I appeared together at a conference at Arkansas State (co-directed by a friend who had been a graduate student with me at NU), and I helped him edit a journal called, you guessed it, Teaching Faulkner. We met at his university’s conference on Faulkner and selected other writers, one year both of us and lots of our friends giving papers on Faulkner and Twain. Sadly, the run of the conference stopped just when the next year was to be Faulkner and Cather—who read each other extensively.

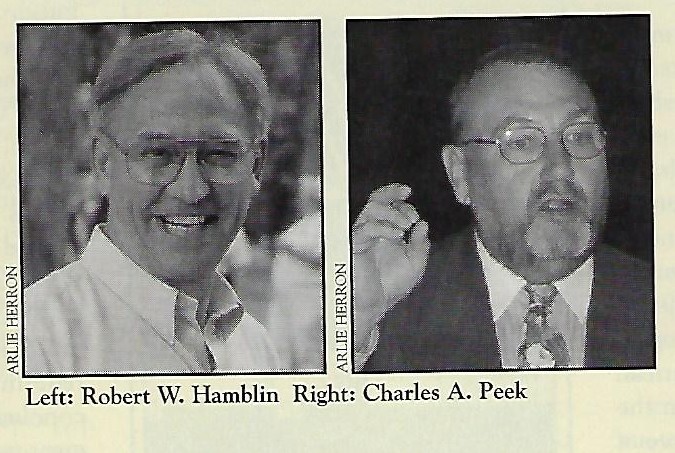

Bob and I, photos in the Southern Register announcement of our A William Faulkner Encyclopedia

We’ve both followed each other’s efforts as poets, writing blurbs for one another, and looking forward to new work, which is how I came to be following his most recent effort—a challenging task of producing a work about Faulkner in verse, Bob from time to time posting one of the poems on Facebook. As I wrote this in early October, I had just received from Bob an email that the project was finished and in publication.

I’m delighted, of course, to see it, with Bob’s poems running the whole gamut of Faulkner’s stories and characters, a unique way of summing up and honoring what is possibly the most extensive body of literary work to be found by a single author. Bob has also written biographies of many of the FY crowd, Faulkner included but also Evans Harrington and others.

But what especially endeared me to this project, even before I saw it finished, was the following from its opening pages:

Faulkner

Commentary in Verse

With Illustrations by Evelyn Mayton

First Edition

First published in 2023 by

Southeast Missouri State University

One University Plaza MS 2650

Cape Girardeau, MO63701

For

my colleagues in the Teaching Faulkner sessions

Faulkner and Yoknapatawpha Conference

University of Mississippi

Jim Carothers

Chuck Peek

Arlie Herron RIP

Theresa Towner

Terrell Tebbetts

Brian McDonald

They taught me much

And for Ann Abadie who shepherded us all

Bob’s spot on about Ann…she was the heart of the conference for all its years, and she and Dale were wonderful hosts.

But Bob, you don’t have to wait to join your beloved Kaye in the hereafter to hear the words Well Done…well done my mentor and friend, my colleague in the Faulkner world we have so richly enjoyed, one of the rewards of which is our friendship, another being this commentary on Faulkner in verse.

Kearney, Nebraska

October 16, 2023

Next blog: Quarterly “In Memoriam” out around All Saints Day.